本の印刷は共同作業でしたが、 ここで見られるように、さまざまな人々が印刷機用の本を準備しています。 JoannesStradanusの後のJanCollaert I、 「本の印刷の発明、 " の 現代の新しい発明(ノヴァレペルタ)、 プレート4、 NS。 1600、 紙に刻む、 27 x 20 cm(メトロポリタン美術館)

印刷機は、間違いなく、近世の歴史の中で最も革新的な発明の1つでした。 15世紀のドイツの金細工職人兼出版社でありながら、 ヨハネスグーテンベルク、 画像やテキストの大量生産を可能にする機械式印刷機の作成で知られています。 活字の技術は、東アジアではるかに早く最初に開拓されました。 11世紀初頭の中国では、 職人の畢昇は、焼き粘土から個々の漢字を作成して、活字のシステムを作成できることを発見しました。後で、 13世紀の韓国では、 最初の既知の金属活字が製造されました。

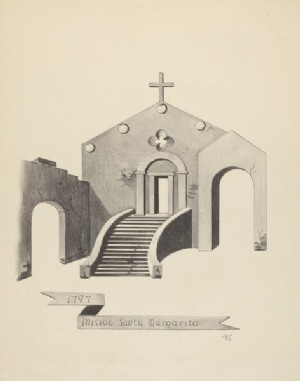

活字で印刷された世界最古の現存する本のページ、 大仏教僧の禅の教えのアンソロジー 、 1377、 24. 5 x 17 cm(フランス国立図書館)

シルクロードを経由した東アジアとヨーロッパの文化間の接触と交流の増加、 13世紀に始まり、 そのような印刷の革新の広がりにつながりました。それはそう、 1400年代半ばまでに、 グーテンベルクは、同じテキストソースと視覚的表現の複数を印刷するための彼の機械的プロセスを考案する絶好の立場にありました。 どれの、 ポータブルでより手頃な紙のサポートのおかげで、 それらが広く流通することができることを意味しました、 デジタル化以前の時代のマスコミュニケーションの初期モードとして機能します。活字の導入と相まって版画の出版は、知識とアイデアの異文化交流のための前例のない可能性を提供しました、 芸術的なスタイルやデザインだけでなく。

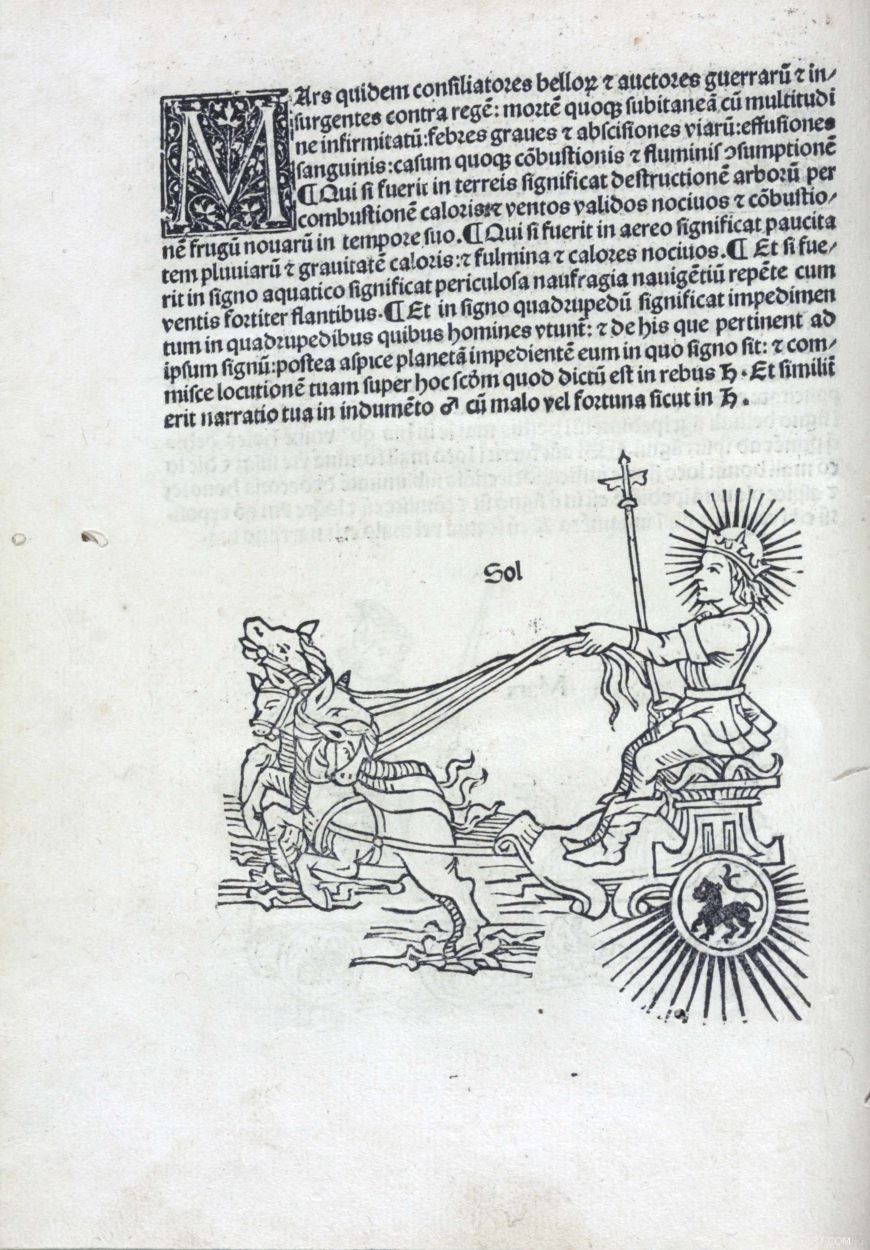

このイラストは、エルハルト・ラートドルトが出版した本からのものです。 アウグスブルクの初期のドイツ語プリンター、 そして73枚の木版画で描かれています。ここに「ソル」または「サン」が表示されます。 」のAlbumasar、 Flores astrologiae (アウグスブルク:エルハルト・ラートドルト、 11月18日 1488)、 画像22(ローゼンヴァルトコレクション、 貴重書・特別コレクション課、 議会図書館)

15世紀以前は、 祭壇画のような芸術作品、 肖像画、 そして他の贅沢品は、これらの絶妙な物を委託するための財源を持っていたのはコミュニティの社会的エリートと宗教指導者だったので、主に裕福な常連客の住居と教会で見つかりました。印刷の再現可能なフォーマットと紙の利用可能性の増加は、成長する中産階級に与えました、 絵画や彫像を購入する手段がなかったかもしれない人、 芸術的な表現を収集する機会。大規模なプロジェクトはまだ裕福な常連客によって資金提供されていましたが、 版画の大部分は憶測で購入されました。結果として、 さまざまなコレクターにアピールするであろうさまざまな主題が印刷物に描かれています。例えば、 過去を研究したいという願望、 文学、 近世ヨーロッパの都市の科学は、版画家に古代史の表現をアートマーケットに提供することを奨励しました。 古典神話、 そして自然界。

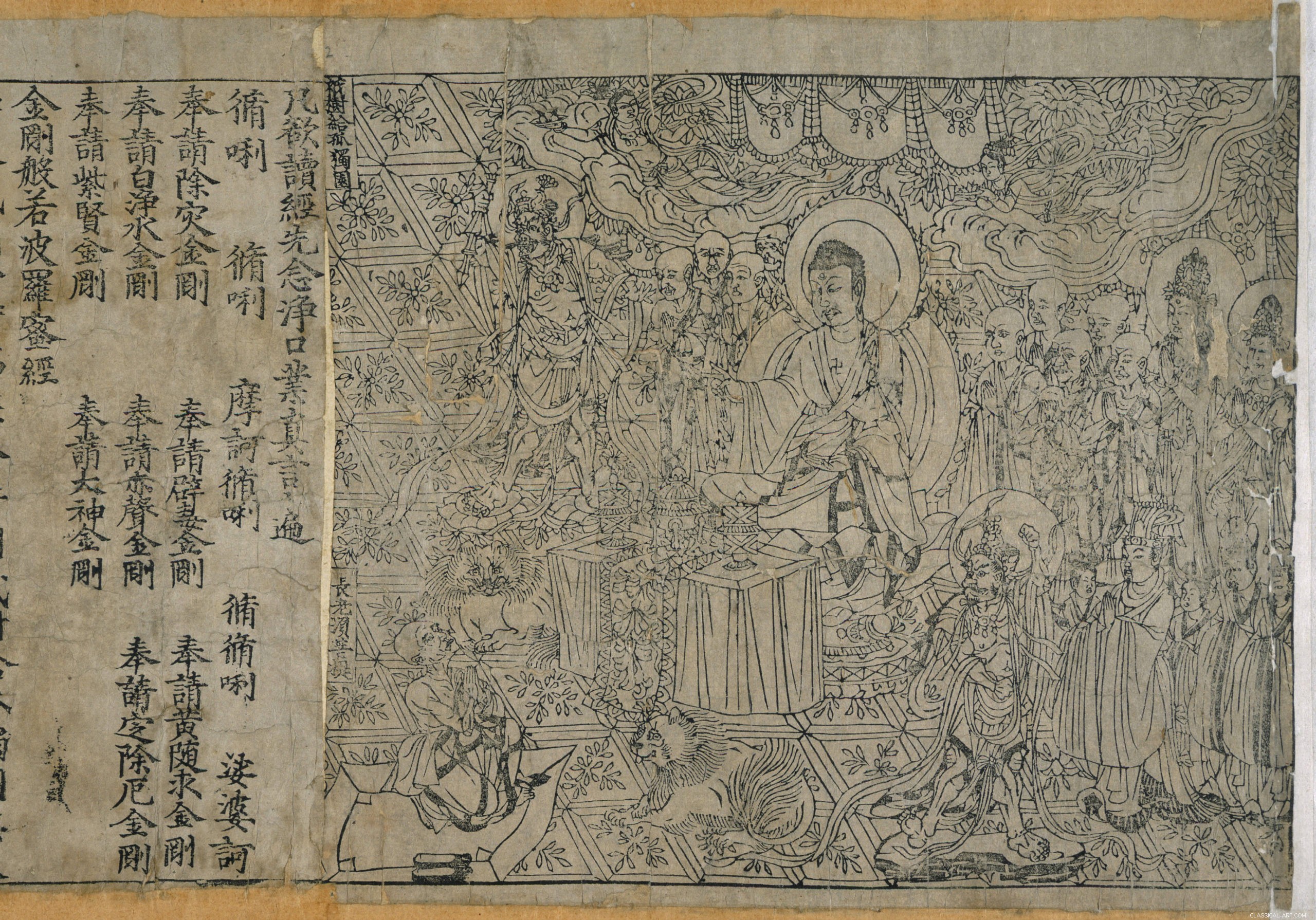

金剛般若経 、 868、 木版印刷の巻物、 莫高窟(または「比類のない」)洞窟または「千仏の洞窟」で発見されました。 」は、シルクロード(大英図書館)沿いの4世紀から14世紀までの主要な仏教の中心地でした。

版画の最も古い形式は木版画です。早くも中国の唐王朝(7世紀に始まった)、 木版は、テキスタイルにテキストを印刷するために使用されました。 そして後の論文。 8世紀までに、 木版印刷は韓国と日本で定着していた。書かれた情報源を印刷する慣行は東アジアのはるかに古い伝統の一部ですが、 木版を使用した印刷画像の作成は、ヨーロッパでより一般的な現象でした。 14世紀後半のドイツで始まり、その後オランダとスイスアルプスの南からイタリア北部の地域に広がりました。

初期の木版画はしばしば宗教的な主題を示しています。ここでは、聖母マリアが死んだ息子を抱きしめているのが見えます。 イエス。南ドイツ、 シュヴァーベン、 ピエタ 、 NS。 1460、 木版画、 水彩で手彩色、 38.7 x 28.8 cm(クリーブランド美術館、 クリーブランド)

ペトルス・クリストゥス、 女性ドナーの肖像 彼女の後ろの壁にプリントがぶら下がっている本の前にひざまずいて(詳細)、 NS。 1455、 パネルに油彩、 41.8 x 21.6 cm(国立美術館)

グーテンベルクが印刷機を発明した後の15世紀の後半、 木版画は、活字で作られたテキストを描くための最も効果的な方法になりました。結果として、 ヨーロッパの都市、つまりマインツ、 ドイツとヴェネツィア、 イタリア—版画が最初に定着した場所は、本の生産の重要な中心地に発展しました。機械プレスを使用して紙に印刷された画像を作成するヨーロッパの方法は、16世紀までに東アジアに浸透しました。 しかし、それは数世紀後の日本の江戸時代に色付きの木版画(浮世絵)が大量に生産されるまで、芸術目的で広く採用されることはありませんでした。

初期のヨーロッパのルーズシートの木版画は、主にキリスト教の主題を描いています。 比較的安価な祈りのイメージとして機能します。今日の美術館は、印刷物を温度管理された箱に保存して、将来の世代が楽しめるようにしていますが、 15世紀と16世紀には、 彼らは折りたたまれ、巡礼者によって旅行中に運ばれました。 本の表紙にカットアンドペーストして、 または家の壁に貼り付けます。その結果、 初期の木版画は、継続的な使用によって破壊されることが多いため、生き残ることはほとんどありません。まだ、 重要な現存する木版画は、この初期のタイプの版画の様式的な特徴を明らかにしています。

この木版画は火事を乗り越えました。それはメアリーが幼児イエスを抱いていることを示しています、 聖人とメアリーの生涯の場面に囲まれています。不明な15世紀の印刷業者、 火のマドンナ 、 1428年以前、 木版画、 ペンキで着色された手、 寸法は不明です(サンタクローチェ大聖堂、 フォルリ、 イタリア)

例えば、 2つの木版画( ピエタ 南ドイツと15世紀初頭のイタリア製 火のマドンナ それが収容されていた建物を破壊した火事で生き残ったと言われています)両方とも、太い輪郭で描かれた人物やその他の風光明媚な要素を展示しています。これらの画像は、最小限の陰影とパターン化を特徴としています。 コレクターが構図の感情的な魅力を高めるために手でペイントを適用することが多いステンシルデザインに似ています。これは、キリストの傷から滴り落ちる血を表す赤いペンキの筋が組み込まれていることで見られます。 ピエタ 印刷。

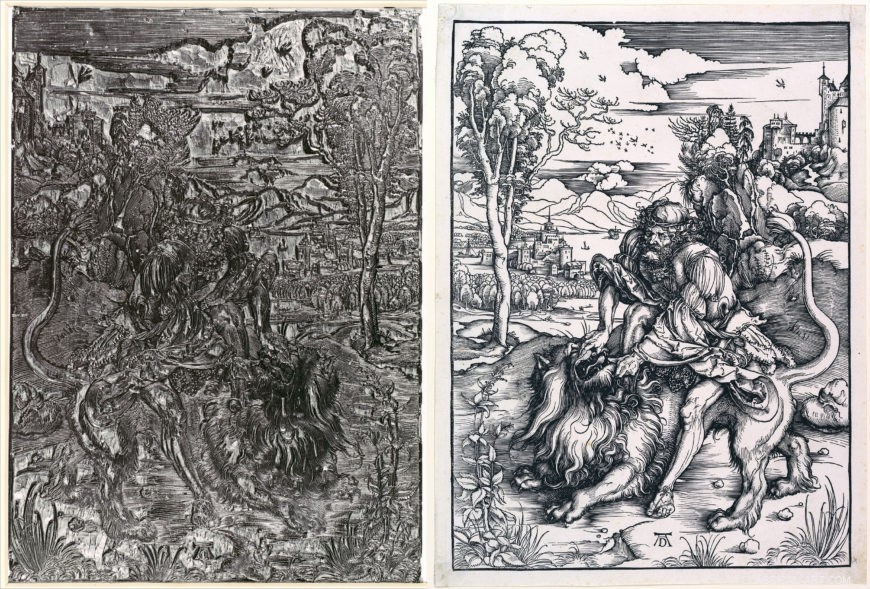

左:アルブレヒト・デューラー、 木版 サムソンとライオン 、 NS。 1497-1498、 梨の木、 39.1 x 27.9 x 2.5 cm(メトロポリタン美術館);右:アルブレヒト・デューラー、 サムソンとライオン 、 NS。 1497-1498、 木版画、 40.6 x 30.2 cm(メトロポリタン美術館)

現代アーティストは、手持ちのガウガーを使用して、木版画のデザインを日本の合板にカットします。デザインは合板の塗装面にチョークでスケッチされています(写真:Zephyris、 CC BY-SA 3.0)

救済プロセスの一種、 木版画は、マトリックスの隆起した表面にインクを塗ることによって生成されます。 これにより、手動または機械的(印刷機)圧力を使用してブロックを紙に押し付けると、組成物の鏡像が得られます。ゴム印はレリーフ印刷の現代的な例です。木のブロックにデザインを作成するには、 アーティストはナイフまたはガウジを使用して、印刷する線と形の間の木材の部分を切り取ります。木の領域を切り取るとき、 隆起した線を細くしすぎないように注意する必要があります。そうしないと、圧力を加えて印象を与えるときに線が折れる可能性があります。 そのため、初期の木版画は大胆な輪郭のデザインが特徴です。

浮き彫りプロセスは、版画の主なタイプの1つです。木版画を作るには、 アーティストがマトリックスの隆起した表面にインクを塗り、 これは、手動または機械的(印刷機)圧力を使用してブロックを紙に押し付けたときに、構図の鏡のような印象を作成します(ニューヨーク近代美術館のビデオ)。

15世紀後半までに、 ドイツの芸術家アルブレヒト・デューラーは、彼の版画に印象的な質感と色調の繊細さを表現する方法を見つけました。彼の中で一連の細い線を互いに近づけることによって サムソンとライオン 、 彼は丘の中腹にある影を説得力を持って表現しました。

このプリントの白い部分はインクが塗られていません、 シーンのハイライトとして機能します。ルーカスクラナッハ長老、 セントクリストファー 、 NS。 1509、 キアロスクーロの木版画(クリーブランド美術館、 クリーブランド)

のような手彩色の木版画の生産によって示されるように ピエタ と 火のマドンナ 、 一部のコレクターは、カラープリントの美的で感情的な陰謀を好みました。 16世紀には、 北ヨーロッパとイタリアの版画家は、キアロスクーロの絵の外観を模倣しているため、キアロスクーロの木版画として知られる色付きの木版画を作成することで、その関心を利用しました。このタイプの図面では、 色紙は、アーティストが光を生成するために白い顔料を追加する中間調として機能します( キアロ )トーンとレンダリングを暗くします( スクロ )ペンでハッチマークを組み込むか、ブラシで暗く洗う領域を組み込むことによる値。同じ概念がキアロスクーロの木版画にも当てはまります。ルーカスクラナッハの セントクリストファー 、 例えば、 2つの異なる木版で作られました。木版1枚、 トーンブロックと呼ばれ、 オレンジ色の中間調を作成しました。 2番目の木版、 ラインブロックと呼ばれる、 黒い線を生成し、 それが基本設計とハッチングです。用紙の印刷されていない領域がハイライトとして機能します。

の例 ニエロ プラーク、 暗いペースト状の物質がはめ込まれた金属表面に刻まれた線形のデザインで。との献身的なディプティク キリスト降誕 と 礼拝 、 NS。 1500、 パリ、 フランス、 銀、 ニエロ、 金メッキ銅合金、 13.9 x 20.8 x 0.7 cm(クロイスターズコレクション、 メトロポリタン美術館)

最初の木版画が作られて間もなく、 凹版の彫刻プロセスは1430年代にドイツで登場し、15世紀の後半までに北ヨーロッパと南ヨーロッパの他の地域で使用されました(凹版は彫刻を含む版画のカテゴリです。 ドライポイントとエッチング)。彫刻は、リソグラフィーのような平版技術が発明されるまで、18世紀の終わりまで版画の一般的な方法でした。彫刻は、金と銀細工の工房の伝統にルーツがあります。 ニエロ プラーク(金または銀の小さなプレート)は、金属表面に直線的なデザインを刻み、それらの刻まれた溝に暗いペースト状の物質をはめ込んで、明確な表現を表現することによって作成されました。

アーティストは、金属板を引っかいてエッチングし、表面の細部を細かく作成しました(ニューヨーク近代美術館のビデオ)。

彫刻プロセスで使用されるビューリン(写真:ManfredBrückels、 CC BY-SA 3.0)

木版画のレリーフプロセスとは異なり、 彫刻は、ビュランと呼ばれる菱形の先端を持つツールを使用して銅板に彫刻することによって生成されます。 V字型の溝が残ります。デザインが完全に切開されたら、 プレートの表面全体にインクが塗られています。次、 プレートはきれいに拭かれ、切り込みの入った線に付着したインクだけが残ります。これで、湿った紙でマトリックスを印刷機に通す準備が整いました。プレスからの圧力が紙をそれらの溝に押し込み、インクを拾い上げます。 その結果、銅板に刻まれた画像の鏡のような印象になります。

これはショーンガウアーの最も初期の彫刻の1つですが、 それは非常に影響力がありました。ミケランジェロもそれをコピーしました。マルティン・ショーンガウアー、 悪魔に苦しめられた聖アントニウス 、 NS。 1475、 彫刻、 30.0 x 21.8 cm(メトロポリタン美術館)

レリーフのデザインを木版に彫るのが難しいのと比較して、 彫刻の技術により、熟練した芸術家は、機械プレスの圧力で壊れてしまうような細すぎる線を作成することを恐れることなく、非常に詳細でスタイル的に多様な構成を作成することができました。ルネッサンス期のヨーロッパで最も偉大な彫刻家の1人は、マルティン・ショーンガウアーでした。彼の 悪魔に苦しめられた聖アントニウス 彼の多彩な彫刻技術を披露します。

マルティン・ショーンガウアー、 の詳細 悪魔に苦しめられた聖アントニウス 、 NS。 1475、 彫刻、 30.0 x 21.8 cm(メトロポリタン美術館)

さまざまなテクスチャを作成するには、 ショーンガウアーはさまざまなマークを使用しました、 長いなど、 アンソニーの左腕をつかむ生き物の鱗を作成するために、クラブの短いU字型の線を振り回す悪魔の柔らかい毛皮をレンダリングするためのカーリングライン。 By incorporating passages of dense cross-hatching across Anthony’s body, Schongauer also gave his figure a three-dimensional presence on the flat paper surface.

Etching likely developed in the workshop of Daniel Hopfer, who created ornamental designs in the surface of metal armor. Attributed to Kolman Helmschmid, etching attributed to Daniel Hopfer, Cuirass and Tassets (Torso and Hip Defense), with detail of Virgin and Child on the center of the breastplate, NS。 1510–20, steel, leather, 105.4 cm high (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Etching

Another intaglio process that developed in Germany around 1500 and remained popular throughout the early modern period was etching. While engraving originated from the craft of gold- and silversmithing, etching was closely related to the armorer’s trade. Etching likely developed in the workshop of Daniel Hopfer in Augsburg, a city in southern Germany. Hopfer discovered that through etching he was able to create ornamental designs in the surface of metal armor.

To etch an iron or copper printing plate, an acid-resistant substance (usually a varnish or wax) called a ground is applied to its surface. With a stylus or needle an artist draws a design into the ground, removing some of the coating each time a mark is made. After the design is complete, the plate is submerged into an acid bath and a chemical reaction takes place. The acid bites into the exposed metal, creating linear grooves. Once the plate is taken out of the bath and the ground is removed, the incised matrix is ready to be inked and printed in the same way as an engraving. Whereas engraving takes considerable manual labor because the printmaker has to carve into the metal plate, in the etching process, the acid does all of that work, and so it was considered an easier alternative to engraving. Artists who were adept at drawing, but not necessarily trained to engrave plates, found etching to be a suitable medium to make prints, since realizing a design in the ground with a needle was akin to drawing with a pen on paper.

Parmigianino, Entombment 、 1529−1530, etching, 27.1 x 20.4 cm (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland)

Just like engraving, which had originated in Germany but quickly became popular among artists in other parts of Europe like Italy, etching also spread throughout the continent soon after its development. Parmigianino was one early sixteenth-century Italian painter and draftsman who tried his hand at etching.彼の Entombment shows off his expressive line work. It appears “sketch-like, ” resembling a pen-and-ink drawing rather than an engraving, which is usually characterized by regularized lines and marks of equidistant spacing and length.

First state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People 、 1655, drypoint i/viii, 38.3 x 45.1 cm (British Museum, London)

Drypoint is perhaps the simplest method for creating an intaglio print. It developed at the same time as engraving in early fifteenth-century Germany, and like other related processes, drypoint attracted printmakers working across Europe. The technique involves using a stylus or needle to scratch into the surface of the copper matrix to throw up a burr. Just as the sides of a furrow or trench dug into the ground will hold drifts of snow, the raised edges of a drypoint line will retain ink. When making an engraving, the printmaker scrapes away the burr in order to achieve clean lines when the plate is printed. In a drypoint, しかし、 the burr is left so that when the plate is printed, it produces a rich, velvety line. Unlike engraving, which can yield hundreds of decent impressions, the delicate drypoint burr wears quickly each time a plate is run through the press. For this reason, drypoint was most often used to add finishing touches to compositions after the primary design had been engraved or etched.まだ、 some printmakers like the seventeenth-century Dutch master, Rembrandt, preferred to work entirely in this technique.

Detail, first state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People, 1655, drypoint i/viii, 38.3 x 45.1 cm (British Museum, London)

の Christ Presented to the People 、 the contours of Pontius Pilate, Christ, and the surrounding soldiers reveal the dense, blurred character of the drypoint burr. Because drypoint created few quality impressions, Rembrandt often reworked his plates, making different states of the same image in order to produce more legible representations. The first state was printed early on in the plate’s lifetime before the burr began to wear. In the fourth state, the once-strong velvety lines have all but disappeared and changes to the architecture are visible. Most noticeably, the balustrade depicted near the upper right does not appear in the first state.

Fourth state, Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ Presented to the People 、 1655, drypoint iv/viii, 35.8 x 45.4 cm (British Museum, London)

Mezzotint rockers (photo:Toni Pecoraro)

The term mezzotint is a compound of the Italian words mezzo (“half”) and ティンタ (“tone”), and describes a type of intaglio print made through gradations of light and shade rather than line. To produce a mezzotint, an artist roughens the entire surface of a copper plate with a tool called a “rocker, ” a chisel-like implement with a semi-circular serrated edge. This tool is rocked back and forth across the plate until it has been completely worked, creating a surface full of burr that will hold ink. If you were to print an impression at this stage, it would appear as a field of rich black. To create a legible image, the printmaker must work from darkness to light with the aid of a scraper—a triangular-shaped blade fixed in a knife handle—and a burnisher—a blunt instrument with a hard, rounded end. By removing or smoothing out the burr, the artist weakens the plate’s capability to hold ink when the plate is wiped, and those areas will print a lighter tone.

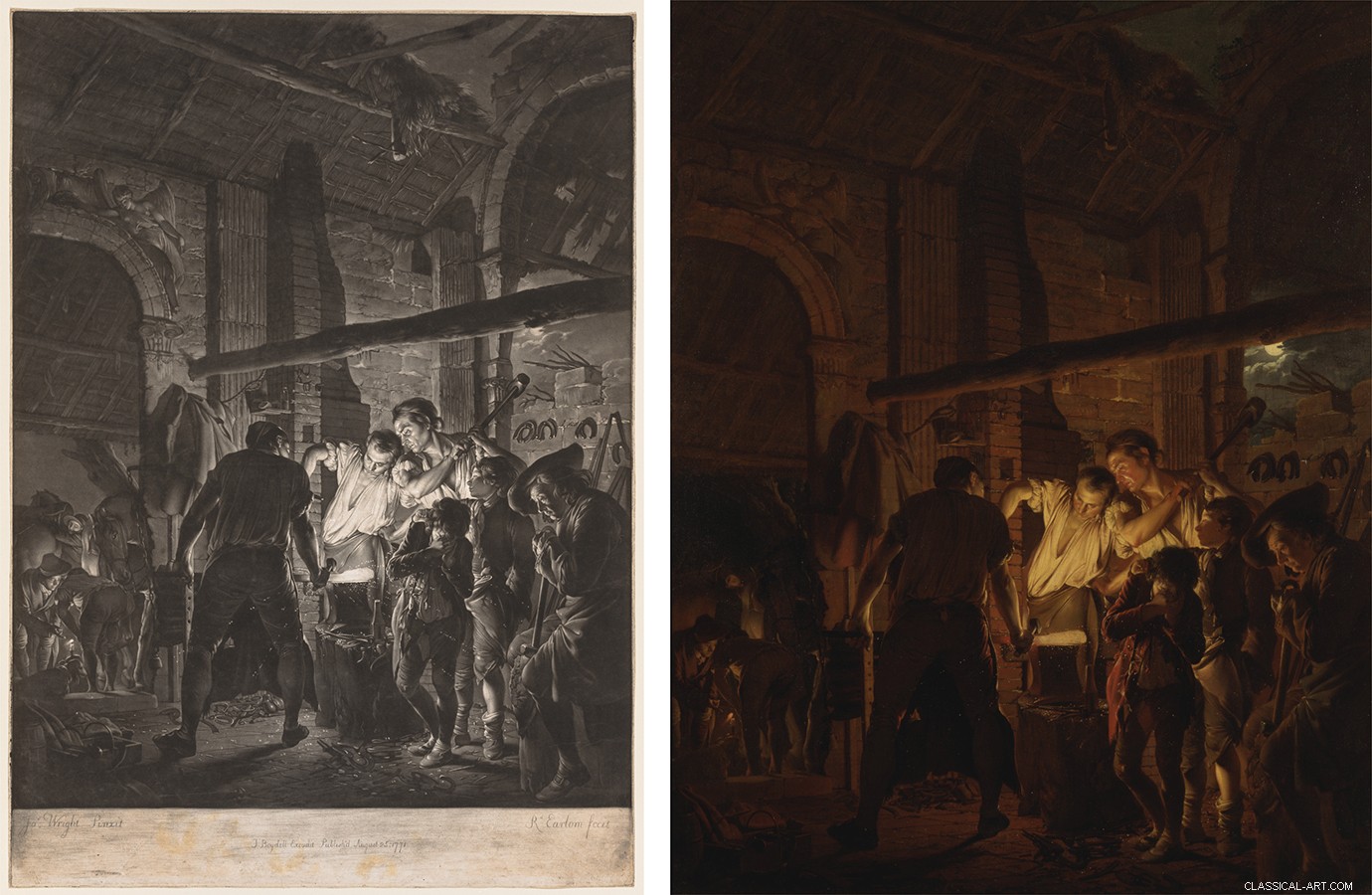

Left:Richard Earlom after Joseph Wright of Derby, The Blacksmith Shop 、 1771, mezzotint ii/ii (Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland); right:Joseph Wright of Derby, The Blacksmith Shop 、 1771, oil on canvas, 128.3 x 104.1 cm (Yale Center for British Art, New Haven)

Although mezzotint originated in Amsterdam during the second quarter of the seventeenth century, it found particular appeal in eighteenth-century London, so much so that the medium was even nicknamed “the English manner.” When the Dutch-born sovereign William III became King of England in the late 1600s, numerous printmakers from the northern provinces of the Netherlands relocated to London in hopes of achieving royal patronage. During successive decades, native English artists learned from their Dutch contemporaries about how to make mezzotints and several technical manuals on the subject were also published locally. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, England had earned the reputation as a prolific center for mezzotint production. Richard Earlom was one English printmaker who had a successful career making mezzotint reproductions of oil paintings. The Blacksmith Shop from 1771 is based on Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting of the same subject. Wright’s pictures, which exhibit dramatic lighting effects, were ideally suited to be translated into mezzotint because the medium could capture the subtle tonal variations and lustrous appearance of his oil paintings.

Aquatint is a variant of the etching process that produces broad areas of tone that resemble the visual effects of watercolor. It involves the use of a powdered resin that is adhered to the plate through controlled heating. As the resin bonds to the plate, it creates a network of linear channels of exposed metal (think of how a cake of mud that is dried in the sun has a web of cracks). Once the plate is bitten by acid, the areas of exposed metal form deep grooves that are capable of holding ink.

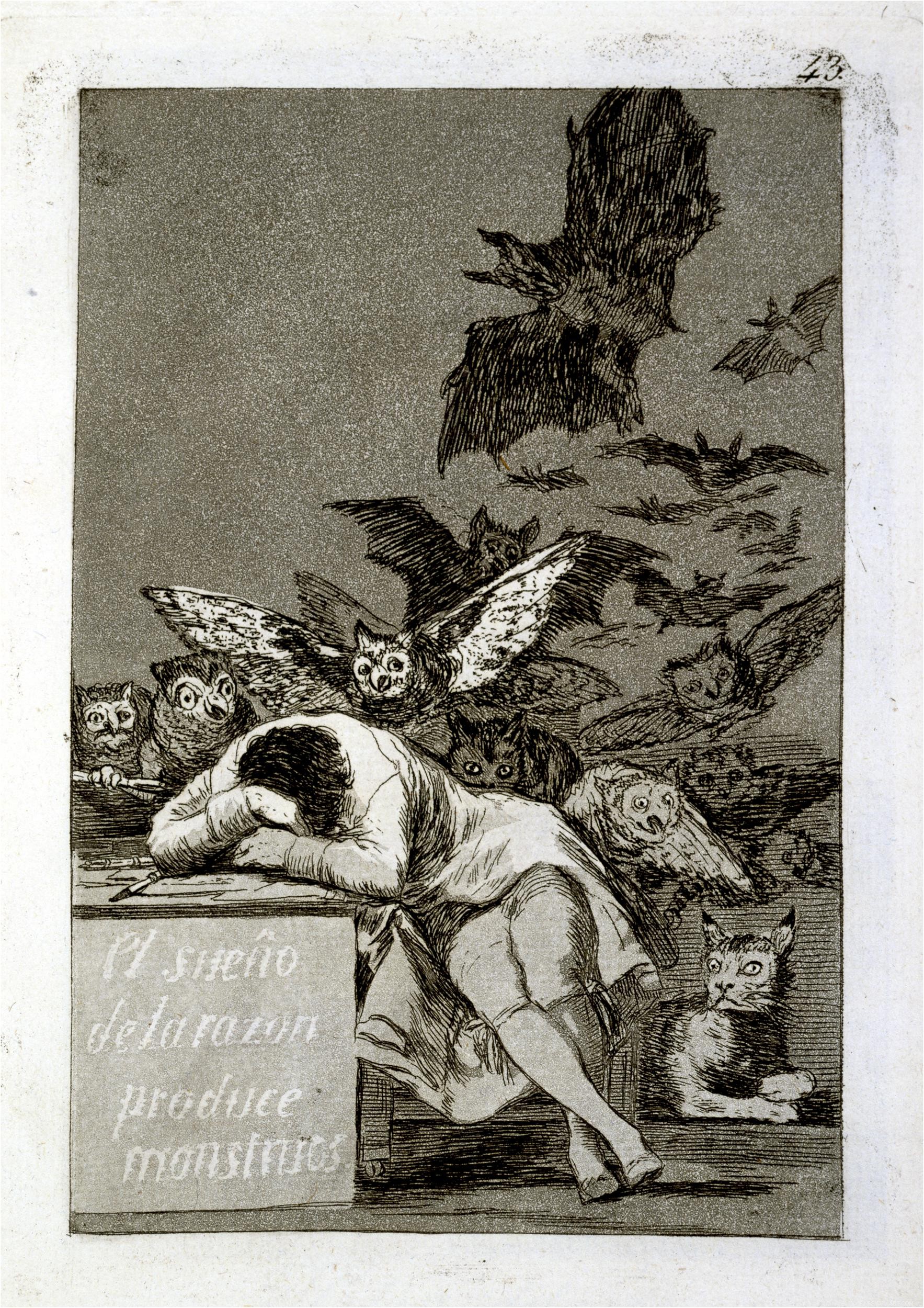

Francisco de Goya is famous for his artworks using aquatint. Goya, Los Caprichos:The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters 、 1799, etching and aquatint, 21.2 x 15.0 cm (British Museum, London)

Aquatint was first introduced in the mid-seventeenth century in Amsterdam.まだ、 unlike other printmaking techniques that found immediate attraction, it would take some time before aquatint became more widely used. By the late eighteenth century, several English etchers had become drawn to the more painterly qualities of aquatint, but the medium arguably achieved its greatest acclaim under the Spanish artist, Francisco de Goya.作る The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters 、 Goya first etched his sleeping artist, the bats, and haunting cat with quick lines. From there, he switched to aquatint to render the ominous shadow that envelops the entire composition and the white letters on the front of the artist’s desk.

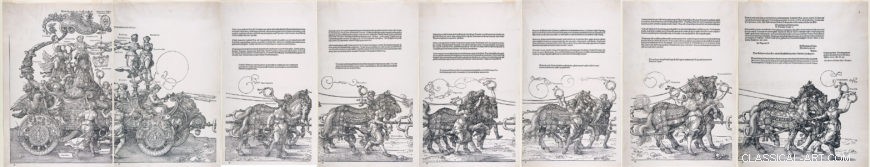

An example of a multi-sheet composition. Albrecht Dürer, Large Triumphal Carriage 、 NS。 1518−1522, woodcut (Metropolitan Museum of Art, ニューヨーク)

Printmaking in early modern Europe was a complex enterprise that involved a number of different agents. It was not always the case that the individual responsible for carving the woodblock or incising the metal plate was the designer of the composition. When Dürer was commissioned by Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I to design a complex, multi-sheet composition of the Large Triumphal Carriage 、 he teamed up with a talented workshop of block carvers to help him execute that grand-scale project. In some workshops, the figure who undertook the physical process of printing the blocks and plates may have only done that job. Additionally, there may have been a separate position dedicated to print publishing, that is selling and distributing the prints. Depending on the size of a workshop and the equipment available, some printmakers or publishers had to contract out some of those tasks.例えば、 if a publishing shop did not own a press, it had to collaborate with another local shop to produce its prints. Early printmaking revolved around a sophisticated network of artists and businessmen, and this legacy is still seen today. Many contemporary printmakers partner with a printing shop to create their work and/or a commercial gallery to exhibit and sell their art.

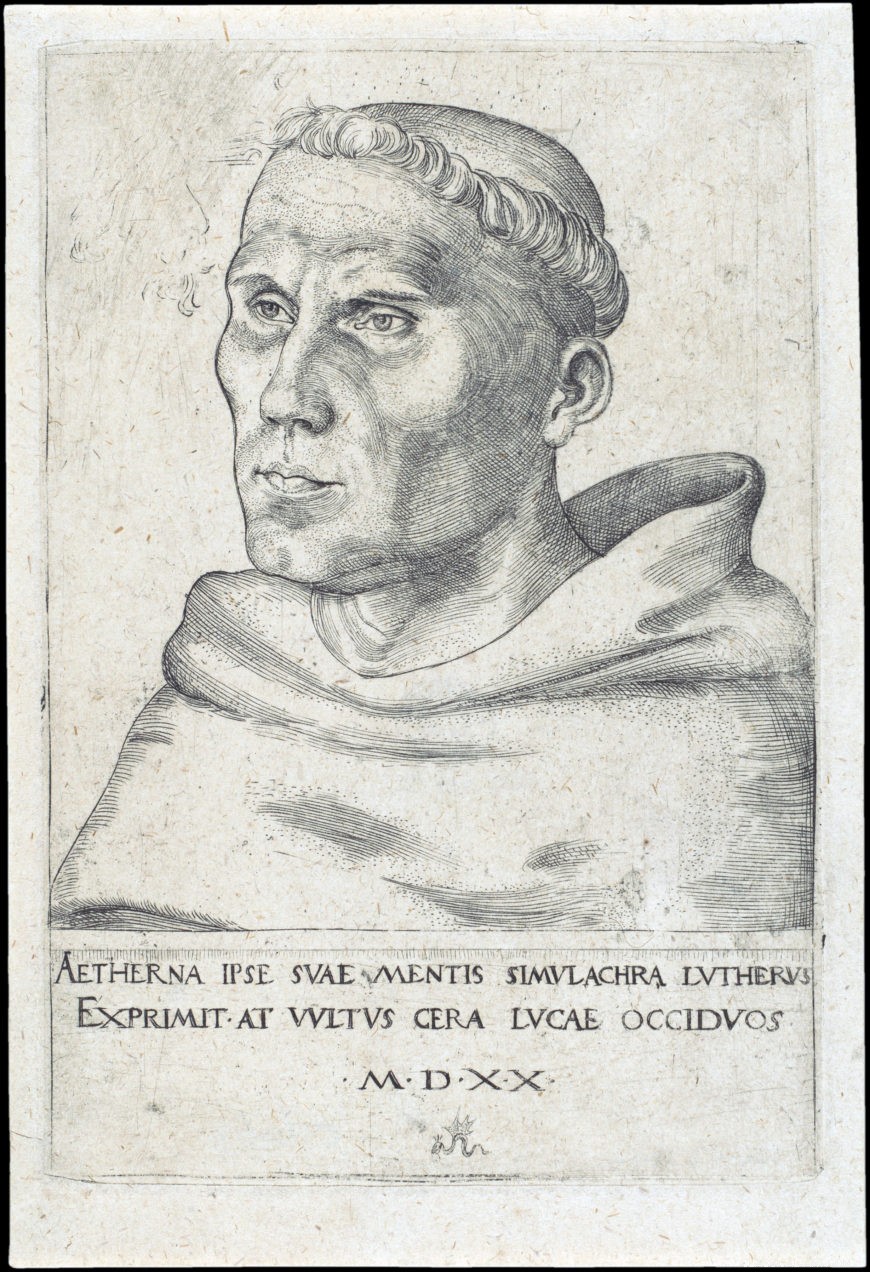

Martin Luther was an Augustinian monk and professor of theology in Wittenberg. He posted his 95 Theses on the door of the castle church in Wittenberg—at least, this is how the tradition tells the story—that took issue with the way in which the Catholic Church thought about salvation, and it specifically took issue with the selling of indulgences. Lucas Cranach the Elder, Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk 、 1520, engraving, 15.8 x 10.7 cm (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The advent of print not only transformed how images were made, but it created new possibilities for art collecting and mass communication. Scholars have long recognized how the mass distribution of printed pamphlets criticizing the Roman Church’s sale of indulgences and the pope’s supremacy along with printed portraits of Martin Luther, such as Cranach’s Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk 、 spurred on a religious revolution in northern Europe by promoting the agenda of Protestant Reformers.

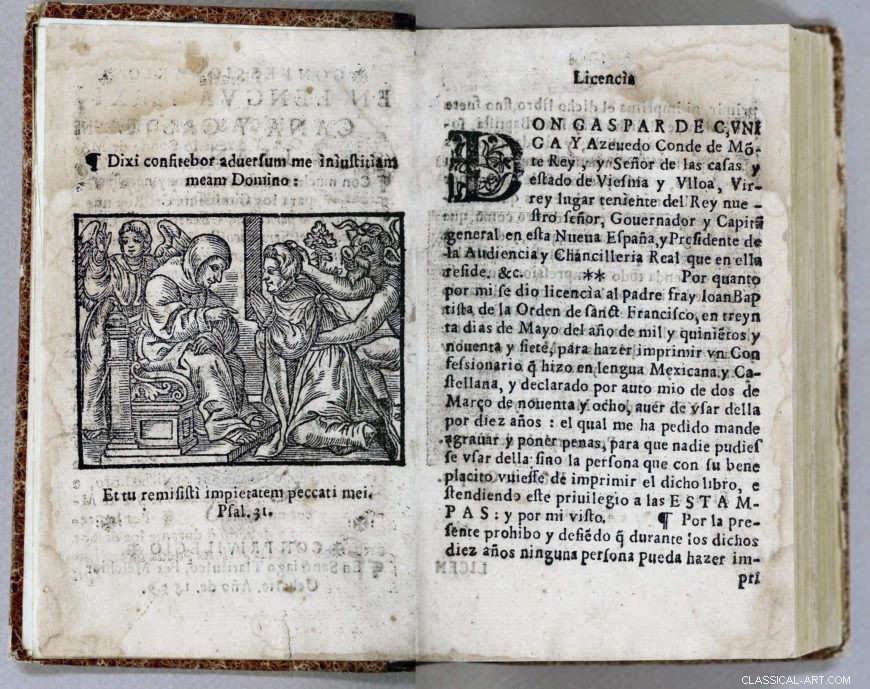

Books made in early colonial Mexico often stressed the importance of images in the process of converting Indigenous peoples. Juan Bautista, Confessionario en lengua mexicana y castellana [Preparation of the penitents in Nahuatl and Spanish] (Santiago Tlatelolco:Melchor Ocharte, 1599), 1v–2r (John Carter Brown Library)

The portability, reproducibility, and affordability of printed compositions contributed to the exchange of information and ideas between cultures of distant geographies. European missionaries who journeyed to the Americas beginning in the sixteenth century brought with them prints of biblical figures that were subsequently disseminated among Indigenous populations in an effort to convert those local communities to Christianity. This kind of imagery also introduced Indigenous artists to new iconographies, visual traditions, and technologies that greatly impacted the artistic production in the Americas.実際には、 during the mid-sixteenth century, the first printing shop was established in modern-day Mexico City and a few decades later Peru transformed into another important center for printmaking in the southern hemisphere. What we consider to be “mass media” today, certainly has its origins in the early modern world of printmaking.

アートの民主化

木版画

キアロスクーロの木版画

彫刻

Drypoint

Mezzotint

Aquatint

The business of printmaking