カーブドピックバナーストーン、 グレンズフォールズ、 ニューヨーク、 6、 000–1 西暦前000年、 縞模様のスレート、 2.7 x 13.6 cm(アメリカ自然史博物館DN / 128)

アメリカ中の学校で古代エジプト人、ギリシャ人、中国人について学ぶのはなぜですか。 しかし、北アメリカの古代の人々についてではありませんか?西暦前6000年から1000年の間の米国の東半分では、 アルカイックとして知られている時代に、 何千人もの遊牧民のネイティブアメリカンがミシシッピ川とオハイオ川に沿って旅行し、住んでいました。彼らが作って残した芸術の中には謎めいたものがあります。 今日バナーストーンとして知られている慎重に彫られた石。それらは一般的に形状が対称であり、中央にドリルダウンされています。 19世紀の考古学者や収集家を率いて、これらの独特の彫刻が施された石は、空中に吊るされた木製の棒に「バナー」として置かれたと考えています。 それにもかかわらず、私たちはまだそれらをバナーストーンと呼んでいます。

カーブドピックバナーストーン、 グレンズフォールズ、 ニューヨーク、 6、 000–1 西暦前000年、 縞模様のスレート、 2.7 x 13.6 cm(アメリカ自然史博物館DN / 128)

バナーストーン、 スレートのように カーブドピック グレンフォールズから、 ニューヨーク、 厳選された石で、その後彫られました。 ドリル、 この特定の石の中心に、 古語の彫刻家は、ワームやその他の生物学的要素によって残されたオフホワイトのマーキングをマークして強調する小さな尾根を彫り、形成された岩の堆積物に埋め込まれた生痕化石と呼ばれるものを形成しました。彫刻された尾根と白化石の痕跡は、スレートの対称的な暗い自然の縞模様を横切って通過します(スレートは2つの地質学的プロセスによって形成されました。 堆積過程、次に変成過程)。薄茶色から暗褐色までの縞模様のそれぞれの異なる色は、岩石構造に硬化した堆積の異なる層を示します。

カーブドピックバナーストーン(リバース)、 グレンズフォールズ、 ニューヨーク、 6、 000–1 西暦前000年、 縞模様のスレート、 2.7 x 13.6 cm(アメリカ自然史博物館DN / 128)

反対側では、 石の縞模様は著しく異なるパターンを形成します、 これを石の両側に異なる堆積パターンを持つ自然発生のスレートにし、彫刻家をさらに引き付けて挑戦し、彫刻されたバナーストーンの湾曲した形がエコーし、暗い縞模様の同心形を強調して、両側を単一の複雑な構成に構成しました。スレートは比較的柔らかい石であり、他の石よりも成形や穴あけが簡単であることを考えると、 それは、バナーストーンを作るために古代のネイティブ北米人によって選ばれた最も一般的な石の1つです。 特にオハイオバレーで。

カーブドピックバナーストーン(上)、 グレンズフォールズ、 ニューヨーク、 6、 000–1 西暦前000年、 縞模様のスレート、 2.7。x 13.6 cm(アメリカ自然史博物館DN / 128)

原石が川で磨耗したり、山腹から採石されたりしたことが判明すると、 彫刻家は「ハンマーストーン」と呼ばれる硬い石を使ってつつき始め、次に縞模様のスレートを挽きます。 現代の学者がこれらの古代ネイティブアメリカンの芸術作品の研究で定義した24の異なるバナーストーンタイプの1つで彼らの作品をモデル化しています。

1929年にバイロンノブロックによって識別された24種類のバナーストーン

の選択 カーブドピック タイプ、 北東部に特有のいくつかのバナーストーンフォームの1つ、 彫刻家は、縞模様のスレートの2つの異なる面の中心に正確に配置されるように構成を行いました。 「翼」を、暗いスレートの帯を通る隆起したエッジに研磨し、 と平坦化、 シェーピング、 パーフォレーションの周りの表面を滑らかにし、 完成した作品をさらに個性化する。認識可能な形に関連する各バナーストーンの個性、 アルカイックの彫刻家と今日これらの石を研究している私たちの人々に認識され、 それらの作成と意味の本質的な要素です。

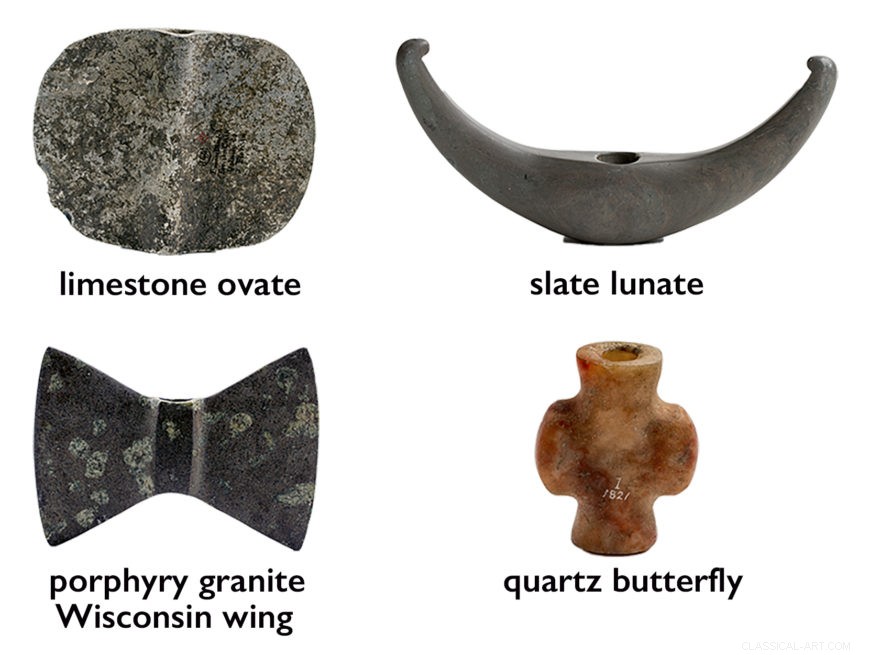

さまざまな種類のバナーストーン(左から時計回り:アメリカ自然史博物館d / 144ライムストーン、アメリカ自然史博物館13/105スレート、NMNH A26077ポーフィリー花崗岩、アメリカ自然史博物館1/1821クォーツ)

バナーストーンは、堆積岩を含む多くの種類の石から作られました。 変成、 石灰岩の卵形のバナーストーンに見られる堆積岩は最も柔らかく、 一方、粘板岩(変成岩)は、月状骨のバナーストーンに見られるバンディングなどの自然の地質学的変化の兆候を示しています。火成岩は最も硬く、マグマが最初に地球の中心部から泡立ったときにさまざまな鉱物の要素が埋め込まれていることがよくあります。 cooled. This kind of complex igneous surface is evident in a porphyry granite Wisconsin wing bannerstone. Some bannerstone (like the quartz butterfly) are made out of even harder material made of minerals and crystals that would have been even more time consuming and challenging to carve . The relative hardness of the stone chosen by the sculptor would have an impact on the kinds of bannerstone forms they would or could sculpt. The thin wings of slate and even granite bannerstones could not be carved out of quartz, while the seemingly thick rounded form of a Quartz Butterfly bannerstone might appear unfinished if it were carved in slate.

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, ジョージア、 6、 000 – 1, 000 B.C.E., 火成岩、 coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

Unfinished bannerstones

Whatever their shape or relative state of completion, all bannerstones were made using river-worn pebbled hammerstones to peck, grind, and polish the surface. Some bannerstones, しかし、 were intentionally left in a partial state of completion known as a “preform” such as a Southern Ovate from Habershan County, Georgia.

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, ジョージア、 6、 000 – 1, 000 B.C.E., 火成岩、 coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

Southern Ovate Preform Bannerstone; Habersham County, ジョージア、 6、 000 – 1, 000 B.C.E., 火成岩、 coarse-grained alkaline, 11.5 x 10.3 cm (American Museum of Natural History 2/2205)

This bannerstone is partially drilled at the spine on one side with a hollow cane or reed that grow along the banks of rivers, and undrilled at the other side. The reed itself is hollow and when rubbed briskly between the hands with the application of water and some sand, can drill through slate, granite and even quartz. With this stone the partial passing of the reed leaves concentric circles on the inside of the perforation and a small nipple visible here that would fall out the other side when the perforation was complete. The medium to coarse-grained igneous rock is left unpolished, just as the ovate form and perforation are left unfinished. Scholars believe that preforms such as these were often buried in this state, or meant to be finished at a later date by another sculptor in a different location. The kind of granite we see here is unique to this region of the Southeast and so would likely have been valuable as a trade good further west along the Mississippi where there was little or no stone available. By partially completing the Ovate form, even partially drilling the perforation the sculptor of this southeastern stone increased the value of the stone while leaving the finish work to whomever acquired this Ovate in this preform state.

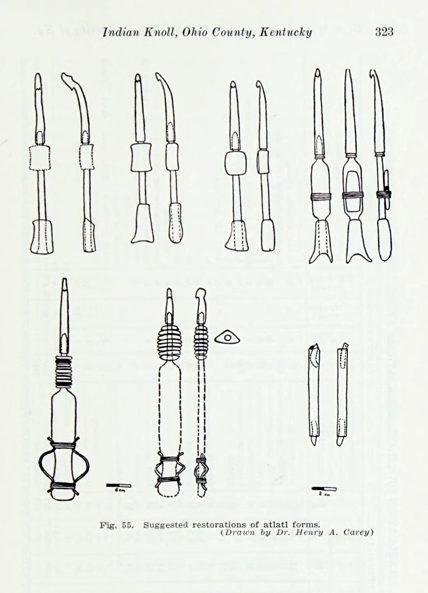

Illustration in William S. Webb, Indian Knoll 、 1946 (publication of his 1937 study at Indian Knoll), p. 322

Hunting tools?

How to use an atlatl, here with an arrow (mage:Sebastião da Silva Vieira, CC BY 3.0)

In 1937, William S. Webb, at the University of Kentucky, with his large crew of Works Projects Administration (WPA) workers funded by the New Deal in the 1930s, excavated 880 burials at the Indian Knoll site in Western Kentucky. Amongst these 880 human burials, Webb found 42 bannerstones buried with elements of throwing sticks known as atlatls. Webb proposed that the bannerstones were weights that had been made to be placed on the wooden shafts of these hunting tools. The first inhabitants of Eastern North America used atlatls instead of the bow and arrow until 500 C.E. The two-foot long shaft of the atlatl could propel a six-foot spear and point great distances with accelerated speed and accuracy. It is a tool invented and used in Eurasia and Africa as early as 40, 000 B.C.E. and ubiquitous throughout the Americas after it began to be inhabited thousands of years later.

Though many scholars after Webb, including myself, agree that many bannerstones were likely carved and drilled to be placed on atlatl shafts, this particular hypothesis raises as many questions as it may appear to answer. For instance why would these Native American sculptors dedicate so much time to an atlatl accessory that appears to have nominal if any effect on the usefulness of the tool? This raises other unanswered questions about the usefulness of beauty and how aesthetics, pleasure, and play are significant, though often overlooked, elements of ancient Native North American art.

Partially destroyed double crescent type bannerstone (American Museum of Natural History DM 333)

NAGPRA

Since Webb’s 1936 excavation at Indian Knoll, Kentucky, remains and belongings of Native Americans are no longer simply there for the taking for the collector’s shelf, college laboratory, or museum case. Especially with the passage of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (known as NAGPRA), funerary remains of Native Americans (bodies and objects placed with these bodies in burials) are protected from being disturbed or excavated unless permissions have been granted by Native communities culturally affiliated with the burials. [1] Native American funerary objects already in federal agencies or museums and institutions that receive federal funding are to be made available to culturally affiliated communities that have the right to request their repatriation. Whatever the aims of post-Enlightenment science or the elucidating potential of the exhibition of artworks may be, these ideological motivations must be negotiated with and in light of the desires, memories, practices, and philosophical underpinnings of the Native American people and their descendants who often buried their dead with bannerstones and other burial remains.

Currently the William Webb Museum has recently removed all photographs of the 880 burials and 55, 000 artifacts that Webb excavated at Indian Knoll in 1936 and will no longer allow scholars to study these remains “until legal compliance with NAGPRA has been achieved.” What “legal compliance with NAGPRA” specifically means for the remains including bannerstones excavated at Indian Knoll is profoundly complex. No living communities of Native Americans trace their direct line (in legal terms, known as “lineal descendants”) to the Archaic people who built this shell mound in which they buried their dead along with valued objects including broken and unbroken bannerstones. With the ratification of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Shawnee and Chickasaw communities that lived in Western Kentucky in the 19th century were forced to move west to Oklahoma. [2] How the William Webb museum will choose to adhere to NAGPRA and what they will do with burial remains from Indian Knoll will set a precedent unfolding into the present about how to collaborate with living Native American communities (even those who are not “lineal descendants”), and how to mindfully regard the past lives of the Ancient people of North American, their human remains along with the multitude of things they made, valued, and arranged in and outside of burials.

Intentionally broken?

Since the 19th century, many bannerstones were found in ancient trash piles known as “middens” as well as ritual burials of things known as “caches” and many more in human burials in subterranean or earthen mound architecture. A large number of bannerstones have also been found broken in half at the spine where they are most fragile due to the thin walls of the drilled perforations.

Broken butterfly type bannerstone (American Museum of Natural History 20.1/5818)

Kill hole in the center of a plate with a supernatural fish, 7th century, Late Classic Maya, earthenware and pigment, 10.5 x 40.6 x 40 cm, Guatemala (De Young Museum)

The intentional nature of these acts of breaking are evident in the placement of pieces together with no sign of wear along the broken edges, carefully arranged with other valuable objects. Archaeologists and historians of the ancient art of the Americas amongst the 8th century-Maya (of Mesoamerica) or 12th-century Mimbres art (of what is today the southwestern U.S.) have often identified this practice as “ritually killing” the object before burial. Though these bannerstones in most cases were intentionally broken by the very people who carved them (most likely just before burial), the meaning and purpose of this act further reveals something about the conceptual and even poetical importance of these sculpted bannerstone forms. Rather than “ritually killing, ” bannerstone makers as well as other artists of Ancient America appear to be repurposing artworks, using them in one way at first, then reconceptualizing them to accompany their dead underground, as a kind of memory-work for the living not entirely unlike the carefully constructed exhibition spaces or storage units of our museums. For the Indigenous people of the Americas the earth itself was often seen as a repository for cultural and personal objects, an underground space that was curated with things that continued to have meaning for the lives of communities for decades and even centuries.

Notes:

[1] More on NAGPRA can be found here and here. [2] Read about the Indian Removal Act at the Library of Congress.